Franklin Evans

Conversation with Greg Lindquist

The Brooklyn Rail, 5 November 2013

In a series of conversations held over the past summer months and into a fall museum installation, artist Franklin Evans spoke with artist and Art Books in Review editor Greg Lindquist. The two discussed the relationships of Evans’s process-based painting installations to Internet media, digital technologies, and the related phenomena of discontinuous focus. Evans’s solo exhibition timepaths opened at the Nevada Museum of Art on October 5, 2013 and will remain on view until April 20, 2014.

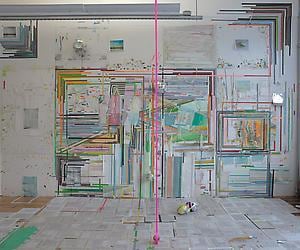

Greg Linquist (Rail): Looking at your studio, with paintings in process on the walls and floor, I am interested in how your work evolves. How do ideas and paintings change over time?

Franklin Evans: Take, for example, this six-foot square painting on this wall [pointing toward a long wall with several large paintings in progress]. It is a smaller canvas in the center, surrounded by several vertical digital prints, each an enlarged documentation of the painting on canvas at the center of the piece. This piece started with the small canvas as the palette on which I mixed paint for other paintings. I then painted on top of the accumulated ground trompe l’oeil elements such as [faux Polaroid, faux lamination of documentation of my past watercolors, and the illusion of tape hovering above the surface]. This piece started as a palette, became a painting, and expanded to an installation while simultaneously embracing an independent system as a painting-collage from which I am now making the fully-painted version. I hope to present both side-by-side in the future.

Rail: This notion of mirror image-like copies call to mind Robert Rauschenberg’s “Factum” paintings, which inspired two consecutive exhibitions you have recently done. Rauschenberg and also Jasper Johns appear to be important touchstones for your work, though perhaps less obvious ones.

Evans: Yes, earlier they were faux Polaroid. Now the increase in scale and size of what I’m printing is taking over, inkjet prints at 17 at 22 inches or larger. It’s amazing what these printers can do. And then to use that as a source for observation to incorporate into the actual painting or the painted painting.

Rail: Rauschenberg was obviously using ephemera and the printing processes of his time in the 1950s. With your work, the nature of the materiality is different and captured in various manners that suggest the ether of virtual, intangible communications. The virtual field of computer screens is important to your work. Translating the multiple windows stacked on top of one another from the inside of a screen into an expanded physical space, in the most non-literal way possible, seems a goal. What is the nature of thinking in this virtual, decentered world? Is it about the way that we often lose focus in this world? Every component is competing for our attention in your installations, which speaks to ways in which we mediate our external worlds, now more than ever.

Evans: Yes, I am interested in the speed that decenters and destabilizes focus. I think that Ryan Trecartin, in the context of the mid-2000s, got close to the speed of how discontinuous focus happens. Although this year in Venice his piece may have been new, it felt surprisingly slow relative to the present. The pacing within his videos remains remarkably fast, but the installation felt relatively static.

Rail: Even though your work incorporates the process and the manner in which we now look at visual images through the mediation of technology, it’s not the predominant medium you choose.

Evans: No, but I would love to use more technology in my work. Another artist who gets close to what I would love to do or see is Jon Kessler, but that also feels slow, and not like my experience on the computer. I work with multiple screens as we have laptops, desktops, and maybe a second laptop, and it’s all going at once. I think somebody’s going to build an environment that’s completely surrounded and multiviewed. I don’t think I’ve seen an installation like Yayoi Kusama’s “Fireflies on the Water” (2002), where she warps installation space. It’s physical, yet not just a single place. It suggests expansion in its use of wall, floor, and ceiling. And through the use of mirrors it also suggests the reflective computer screen, which parallels the virtual realms we now also occupy. I would like to see the compression of Kusama paired with Trecartin’s speedy video as medium. It may require a waiver for claim of injury due to dislocation. You could get hurt! Somebody will do this work I am envisioning, and I hope it’s far beyond a Disney spectacle. Who knows who’s going to do it?

Rail: So why do you continue to emphasize paint as your medium rather than a technological media?

Evans: With my work, I am interested in the materiality of painting. I like those kinds of beautiful painting marks that can be stretched and reinterpreted by digital media. So I combine inkjet printing in front of the other painted things. The materialness of painting with the digitally printed matter is so important to how my work evolves.

Rail: You are hybridizing painting and inkjet prints of a photograph of a painting –

Evans: Over a canvas, that then becomes the source for the completion of the object because I couldn’t have envisioned what that would be like without the materiality of the pigment print. I couldn’t have painted that from looking at a reflective, shiny screen. I need to see the scale of it printed. I need to see a blocking of already-painted information alongside its digitally-altered documentation. It has become more about using these devices to make paintings that are incorporated into an environment. I could not have envisioned paintings and environments without materiality.

Rail: You need the physical tactility and the immersive, phenomenological experience of your body in a space, walking around an object, as well as the objectness of the space itself.

Evans: Yes, it’s the scale of the body to the environment. I think that brings us back to our previous conversations about Daniel Buren, in a way. I can’t make these paintings without considering where they’re going to be. I can make them in a studio, but they will look very different in other environments. If I know in advance that I will be doing a show at a particular space, it is necessary to consider the light of the space and also its architectural specificity.

Rail: The specific architectural aspects of an exhibition space are an integral component in your work.

Evans: When I think of site specifically, the specific location is considered. For example, in the PS1 Greater New York (2010) exhibition, I was given a room that I didn’t know the precedent of – that it once enclosed Gordon Matta-Clark’s “Doors, Floors, Doors” (1967). Colby Chamberlain alluded to that in his review, which I’ve since absorbed. Matta-Clark’s collapse and expansion of space preceded my parallel consideration in my PS1 “timecompressionmachine” (2010). My ignorance of the room’s history allowed me to explore the rich content of time again.

I also engage with architectural challenges such as a column blocking a view or my 2014 New York exhibition [forthcoming Ameringer McEnery Yohe] in a space with a beautiful window. I’m thinking about how I could travel out to the sidewalk without breaking the window, and how I’d tunnel the light in and possibly negate the immediate seduction of the window.

Rail: So, the site acts upon your process?

Evans: I’ve been in my studio for 15 years, but I loved moving to the Marie Walsh Sharpe studios for a year. I didn’t choose that space, but that space allowed and forced me to think about new ways of working. Maybe it’s from the architecture of it. After my year at Marie Walsh Sharpe, I recognized my unconscious capacity to absorb and copy. Similarly, without knowing Rauschenberg and John that well, I’ve absorbed several of their interests and approaches. Specifically at Marie Walsh Sharpe, I did many crossing compositions, and my studio view was of Manhattan Bridge entering at a diagonal, intersecting a more frontal rooftop to create a crossing. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was impacted by my view and what I was around. I think the site acts upon me a lot.

But I also act upon it, getting rid of, creating, or using a column, for example, in a different way to create a new architectural pathway. Last year I made an installation at Lehman College for the exhibition Space Invaders that referred to Robert Irwin’s 1975 Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago column/room. Through the gesture of tape around the floor of the room and through the removal of all the art in the room, Irwin highlighted the column in a room that contained no columns. My columns were constructed of printouts of installation history and of the other installation artists in the Lehman College exhibition.

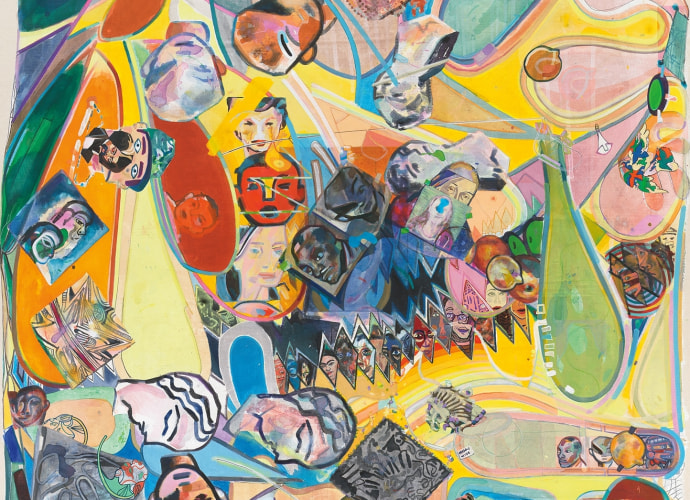

We have also talked about the DECENTER (2013) exhibition at the Abrons Art Center – the 100-year anniversary of the Armory Show. My contribution “bluenudedissent” (2013) was a piece that was driven by the premise of the show. Making a piece about artists now and then, 100 years after the 1913 Armory show.

Rail: Do you think people appreciate it differently because there was a theme you had to incorporate?

Evans: Yes, I used images from art history that I would mostly not have explored at that time. I wouldn’t have looked up all those artists to make an artwork; I wouldn’t have looked up the legacy of the Armory. It was almost like an assignment [laughs] and this sounds really stupid – an assignment that I carried out – but the piece ended up being really interesting. It is something I need to think about more and I have yet to build upon. For DECENTER, I received an architectural gift of installing in and around a somewhat awkward wraparound staircase with a central vitrine. The location and function of the stairs ended up being amazing – the center of the show.

Rail: The center of the decentered show? [Laughter.]

Evans: Exactly! And you havd to walk around it to experience it physically and texturally.

Rail: Well, discussing site-specificity brings to mind not only Daniel Buren but also Robert Smithson, who has been a formative influence on you. Can you say something about how he influenced your thinking and work?

Evans: Smithson has had a link to a lot of us – think about videos of him cagily discussing ideas and images of him walking on “Spiral Jetty” (1970). The library piece I built – the trompe l’oeil library “felibrary2012to1967” (2012) – was born out of finding the index of Smithson’s library.

Rail: From the 2005 Robert Smithson retrospective catalog?

Evans: Yes. I also did a Smithson version by trying to find the highest resolution image of the cover of each book on the Internet, attempting to use the appropriate edition. But sometimes I couldn’t find the appropriate edition and my library was born out of that lack.

Rail: But it wasn’t only his library of books; it was also his record collection, containing an array of influences from Black Sabbath to Waylon Jennings. Some of Jennings’s songs were used in a video finished by Nancy Holt in 2004 from their 1968 trip to Mono Lake.

Evans: Yes, this amazing collection raises a lot of issues about what that means. Is it a curated project? There’s a link to the idea of things ending through entropy, and a desire to preserve and extend an idea about Smithson. With his great work “Spiral Jetty” (1970), it is my understanding that there was no intent to conserve it and we have, as a culture, a desire to immortalize it.

These contradictions are sexy ideas. How do we set up a situation in our own work that can explore these ideas? With the limitations of mostly being a studio artist presenting studio as a subject, I try not to treat the studio preciously. I let paintings live on the floor and erode, I take pictures of them, and start again. Some of the other stuff I wish I could do is experiment more with external elements, things that are built outside, and let time happen to them.

There is an entropic aspect of having paintings live on the floor, as well as tiled press releases of shows you’ve seen. That reminds me of Dorothea Rockburne piece discussed in the High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting, 1967-1975 exhibition catalog (Independent Curators International/D.A.P., 2007). David Reed interviewed Dorothea Rockburne about this piece that was installed on the Bykert Gallery’s parquet floor. In this exhibition, Rockburne painted the entire floor white to match the walls, thus extending the wall and the ceiling to the floor. Throughout the exhibition, visitors created a painting with the scuffs of their footprints, which accumulated over time.

Evans: To reveal the parquet again?

Rail: I don’t know if it went that far. But those marks made by the gallery traffic were an incredibly entropic act if you assume that an exhibition should remain pristine. This act evokes our discussion about the processes of the press releases on the floor falling apart during the course of your exhibitions.

I’m curious how the floor functions in your work. A painting begins in the studio on the floor and then is moved to the wall, and then maybe back to the floor. Is this another part of the process of dismantling the picture frame?

Evans: Using press releases to expose the extent to which I explored NYC exhibitions started as an expansion of the frame. At that time I hadn’t engaged with the floor other than as a student when I worked on my dorm studio floor. I covered the floor with acrylic paintings. It was functional the, but I stopped when I got a studio with walls [laughs]. The press releases were a simple expansion of the frame – the frame of thought and also the visual frame onto the floor and into the installation space.

Rail: After you complete an installation, do you consider it one whole piece or multiple pieces that will then be broken apart and distributed?

Evans: At some point, I would love for it all to be one thing some place, not stripped apart. It’d be really great. Mostly now the parts become isolated into private collections as paintings or sculptures, or reassembled later with new explorations into the next installations.

Rail: How does the system function as a whole? Is this system porous, and fluid, and flexible, and permeable, or is it fixed like a singular photographic image?

Evans: It’s more fluid, but there’s some part that wants fixedness. Even though most everything about what I do and what I’ve been doing is not very fixed. But we’re adaptable! [Laughs.] When I look at this wall in my studio right now, maybe in two weeks it’ll be different.

Rail: What will happen with your installation at the end of the timepaths exhibition at the Nevada Museum of Art? Can you talk about how you have approached the massive scale and size of this museum space?

Evans: The installation is at a significantly larger scale than I have ever worked, particularly because several walls are around 30 feet tall. One wall is 39 feet wide by 28 feet tall. As a part of the installation, this wall becomes my largest painting to date. I usually do scale studies for exhibitions on the computer, with the likely layouts of the elements I collage and build into the space. For this particular wall, I started with the largest painting on canvas from the studio 144 by 72 inches. I pasted a jpeg of this painting onto my scale study in Photoshop and immediately recognized how small it was relative to the wall. It forced me to consider much larger elements: shapes of painted color and forms embedded in the paintings and also extending from the dislocating architecture of the room (walls that tilted out). I added four, 5 by 20 feet canvas pigment prints of distorted documentation images of my library piece, “felibrary2012to1967” (2012). These effectively expanded the visual field to meet the scale of the room and walls. I am nearing the finish of the installation and it is remarkable how much the scale study and the photograph of this large wall painting match up!

I have gained a remarkable material insight into making such large-scale work. Timepaths ends April 20, 2014, but its future began before its installation. Ideas had already begun to be explored in my New York studio prior to my travel to Nevada for installation. Six new paintings began in the later summer, which are not part of this show. With the knowledge gained from the process of this installation, I will return to my New York studio to engage with a past – ready to be altered – for my future projects.