EMILY MASON | FORBES

Emily Mason Connects Visitors To Height Of Abstract Expressionism In New Show At Miles McEnery Gallery

11 January 2021

I Heard The Corn, 1979, Oil on canvas 54 x 52 inches.

Courtesy of the Emily Mson and Alice Trumbull Mason Foundation and Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY.

Mason came of age in the 1940s-1950s. Her mother was an “on-the-scene” painter with whom she regularly attended social engagements at the Eighth Street Club where Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler, Mark Rothko and others could be found. Josef Albers and Piet Mondrain were friends of her mother’s. Mason’s family was particularly close with Sally and Milton Avery, as well as Willem and Elaine de Kooning.

Mason credits the small female contingent of the Club, especially Elaine de Kooning and Joan Mitchell, with empowering her to chart her own stylistic course after having been encouraged at Cooper Union, where she attended college, to maintain a more rigid developmental trajectory in her practice.

As a female artist having grown up hanging around de Kooning and Mitchell, moving out of New York to… anywhere else, just wouldn’t do.

Elaine de Kooning annually gifted Mason and her husband a painting. That’s reason enough alone never to leave.

Mason painted and taught at Hunter College right up until just before her death.

The 20th Street studio remains exactly as Mason left it—a rare and remarkable extant example of the Chelsea studios of the era, left intact in a manner akin to the Donald Judd or Juan Miró foundations–the latter of whom Emily’s mother had a studio adjacent to in the 1940s, and whose art trades are hanging in the 20th Street studio.

Of course.

The studio will hopefully reopen for tours once the pandemic subsides in New York; "Chelsea Paintings” is open at Miles McEnery Gallery's 520 West 21 Street location.

Visit milesmcenery.com for hours and information.

Chad Scott —

Everyone who’s ever been to New York at one time or another has had to ask for directions. Even in an age of smart phones and Siri, visitors to NYC still need help finding the box office, correct subway station or Insta-perfect mural.

This can be intimidating considering New Yorkers’ gruff reputation. It shouldn’t be. While blunt, New Yorkers are almost always helpful.

To break the ice on your next trip to New York, ask a local for these directions: “how do I go from Elaine de Kooning to Nari Ward in one stop?”

On second thought, maybe not.

That’s more of a riddle. New Yorkers won’t take as kindly to those.

The answer is Emily Mason.

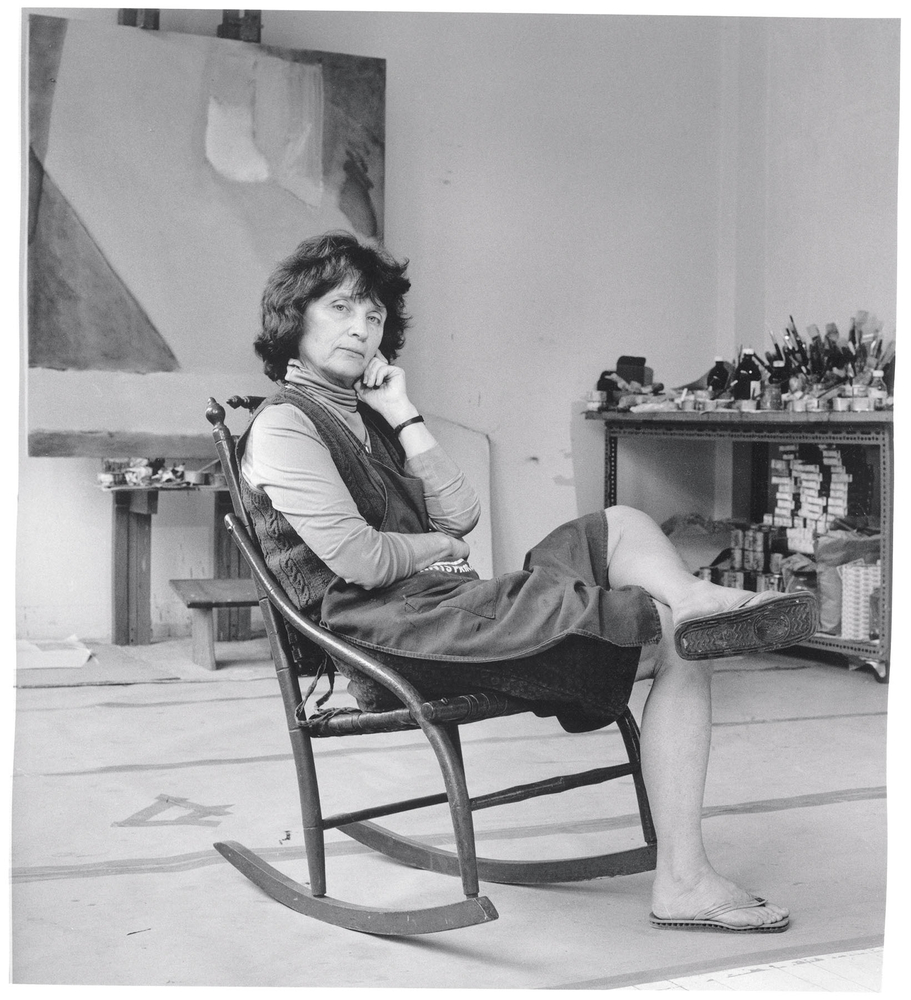

Emily in her New York City studio, 1991. Photographed by Tommy Naess

Mason’s astonishing background includes both having been regularly babysat by the Abstract Expressionist icon who was a family friend and mentoring generations of contemporary artists, including Ward, one of the most highly-regarded working today.

Mason (1932-2019), not her influences or protégés, takes center stage now at Miles McEnery Gallery where her first posthumously organized exhibition, “Emily Mason: Chelsea Paintings,” reveals her large, joyful works, drenched edge-to-edge in vibrant colors through February 13.

“Chelsea Paintings,” explores the career delineation that occurred when Mason moved her studio practice to a sun-soaked, 4,700 square foot Chelsea loft in 1979. She moved from the 12th-and-Broadway space she had shared with her husband, the painter Wolf Kahn, since the 1950s to her own floor-through loft located on the 11th floor of a former garment factory on 20th Street built in 1906.

From then on, regardless of where Mason started a piece, she would always bring it to the Chelsea studio to ‘finish’ it in the distinct light and aura found there.

Featuring 22 works primarily created between 1978 and 1989, “Chelsea Paintings” coincides with a retrospective at the Bruce Museum in Connecticut on view through March 2021.

“She was a petite woman with delicate features and had the presence of someone who is spiritually connected to her environment,” contemporary artist and mentee Marela Zacariastold Forbes.com of Mason. “Emily’s spirit was always awake and present. She noticed everything around her and had a soft way of interacting with the world with joy and wisdom.”

Mason’s “joy” and “wisdom” shine in the “Chelsea Paintings.” A grouchy, insecure artist could not have created this work. These paintings are the result of an artist deeply in love and committed to her craft, sure of herself and what she is doing.

Despite Mason’s assuredness in her own voice, she never forced it on students.

“She was entirely interested in what you wanted to discover and that was what was really great–you felt like she was there in the discovery with you,” her star pupil Ward, whose relationship with Mason began in her beginners’ painting class, told Forbes.com. “She really wasn't interested in pushing a dogma on you, or a particular way of working. The idea was, trying to figure out how, for every artist, what road they needed to take and what path their vision was going to direct them; she was a facilitator in that.”

Steven Rose, her longtime studio assistant and now director of the Emily Mason and Alice Trumbull Mason (Emily’s mother) Foundation, concurs, telling Forbes.com that, “she never wanted people to work like her.”

“Emily’s most important teaching both in art and life was how to connect with your intuition,” Zacarias recalls. “She led you in finding your own voice and becoming aware of the uniqueness of your own being. She provided physical and mental space to let intuition take over. She knew how to nurture your interests and offer suggestions gently and indirectly.”

Mason’s support of her students could be more tangible as well. Both Ward and Zacarias remember Mason gifting them and other students better art supplies than they could afford in their college days.

Her devotion went far beyond what could be purchased at the supply store.

“I worked full-time as a night security guard and would leave work to go to her class,” Ward remembers of his early days painting when he was determining whether or not to pursue an art career. “Since there was about a three-hour gap, I would often go to the Hunter College library to take a brief nap. Once I overslept and was late to class. When I explained to Emily that I couldn’t set my alarm in the library and overslept, she offered to come and get me to make sure I would not miss class.”

Through her students, Mason comes across as nurturing, generous, empathetic. She wanted each individual to find her or his own way. Except when it came to one particular aspect of art about which she was certain.

“Never move away from New York,” Zacarias remembers her mentor advising adamantly. “Emily was a true New York artist, always absorbing the energy of the city and channeling it into her work. Even until the last year of her life, she always made the trips to museums and galleries to see the work of other artists. She never missed an opening of Nari Ward, Steven Rose, Sandy Wurmfeld (who invited her to teach at Hunter College) or one of mine.”

Considering her upbringing during the zenith of the Abstract Expressionist movement when New York asserted itself as the center of the art world, how could she leave?