Amy Bennett | Hyperallergic

"In Praise of Painting’s Ambiguity" by John Yau

27 July 2019

Shortly after my review of Amy Bennett’s exhibition at Miles McEnery Gallery appeared on the Hyperallergic Weekend, I got an email from Mollye Miller, who, I later learned, is a photographer and poet living in Baltimore. In fact, she and I were published in the same little magazine, Prelude, edited by Stu Watson, but not in the same issue. But all of what I know of her came after I read her email.

It is not unusual to get a response from a reader, and it can vary from outrage and name-calling to praise and questions. I never know what I might learn or have to endure. I have heard from relatives of the artist, most often when he or she is deceased. I have been corrected when I have gotten something wrong. I have been disputed, chastised, and, as I said earlier, called all sorts of names, none of which are worth repeating. Still, I read whatever is sent me, knowing it might ruin part of my day.

I frequently don’t know where I might see an exhibition that I will end up reviewing, and I generally don’t know the artist I am reviewing personally. Whenever I am invited to give a talk or reading in a different city, I try to see what might be in the local galleries or museums, and this has often led me to write a review. In the case of Amy Bennett, the show was not open the day I was in Chelsea, walking around and looking at art. My wife, Eve Aschheim, was there the next day and was let into the gallery, even though the show had not opened and the work was still being installed. All the paintings sat on the floor, leaning against the wall. Some of them were quite small, and each was in a deep, protective box. Despite all this, the work caught her attention.

When Eve got home, she told me that I should see the show, which opened the next day. As far as I know, there was no buzz about it, though I distrust that kind of noise. I did not go to the opening, but waited until the following day to see the show. I go to nearly all the shows that Eve recommends, though we don’t always agree on the merits of what we saw.

This is a roundabout way of getting to Miller’s email, which contained the following observation:

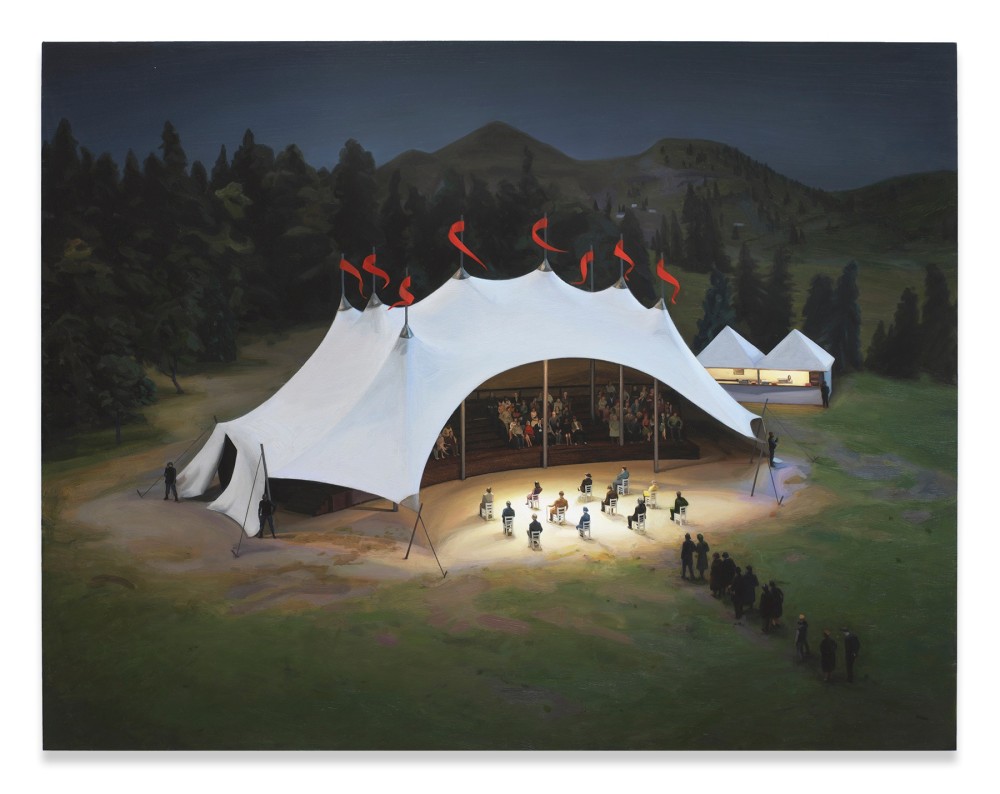

One thing. When you described Bennett’s painting “Our Town” you said that you were confused, albeit delightfully, about what was going on in the painting. I have a theory about this painting I would like to share. I believe in this context, it makes the painting even more disturbing and poignant.

Our Town is one of my favorite plays of all time so I know it well. I believe that Bennett’s painting is depicting Act III of the play, the graveyard scene. In this act, rows of chairs represent gravestones and the people sitting in the chairs represent dead people from the town, Grover’s Corners. The dead people sit still in their graves and look at the living. [Thornton] Wilder says that they get bored looking at the living but they watch them anyway. The row of people queued up behind the chairs/graves are visitors coming to pay respect to their dead friends and relatives.

Bennett, I think, chooses this particular scene to show the garish nightmare of modern “our town” America these days. I think she is showing us the very real, though mostly understated, fear and anxiety we Americans have about being in public places together in this epidemic of mass shootings in small towns. What’s so interesting about this scene to me is that the theatre audience is watching the dead as spectators, and the dead (actors) are watching them, foreshadowing a mass grave of these townspeople. Yes, the militiamen are protecting the audience but they are also weaponizing what would otherwise be a peaceful outdoor summer show.

I’ll add that I like the literal “red flags” Bennett added to the top of the venue. It’s also peculiar and disconcerting that the audience is mostly covered with the circus-like tent and the actors are uncovered and vulnerable. Who’s watching who, and why.

This is the kind of email/letter every reviewer hopes to get – one that opens your eyes and gets you to reconsider what you wrote. Miller’s letter made me appreciate Bennett’s painting differently by enhancing and contextualizing its details.

At the same time, and this is what I think is important about Miller’s insight: Bennett does not require that the viewer know Wilder’s play to experience the painting. It is not based on insider information. In fact, I believe that one could arrive at very similar thoughts and feelings about Bennett’s painting without knowing the source.

Miller’s email brought up an issue that I have been mulling over for years. It has to do with Philip Guston’s rejection of abstraction in the late 1960s. This is how he framed it in a lecture he gave at the University of Minnesota (March 1978), which was first published in Philip Guston (London, Whitechapel Gallery, 1982, 49-56):

Years back, in the late forties and early fifties, I felt that painting could respect itself, reduce itself to what was possible; that is, to paint only that which painting, through its own means, could express. I enjoyed that short-lived period. The reverberations of such paintings could be heard. But in time I tired of this kind of ambiguity. There were better things and too much sympathy was required from the maker as well as the all too willing viewer. Too much of a collaboration was going on. It was like a family club of art lovers. This disenchantment grew. I knew that I would need to test painting all over again in order to appease my desires for the clear and sharp enigma of solid forms in an imagined space, a world of tangible things, images, subjects, stories, like the way art always was.

If “too much sympathy was required” during the late ‘60s, a period dominated by Conceptual Art, Minimalism, and Color Field painting, I wonder what has changed since then. The polemics of that tumultuous period – which Guston resisted and did a lot to undermine – has been replaced by a new polemics, which are not rooted in the formal but in the political and social. Frank Stella’s literalism of the 1960s (“What you see is what you see”) leaves no room for the imagination or for speculation. There is no place that opens up, where viewers can reflect upon the object in front of them. This kind of looking has been replaced by an insistence on the factual, which also leaves little room for much else. You can’t argue with the facts, as they say. But, as Ann Lauterbach writes in her book of poems, Spell (2019): “Facts aren’t the same as persons.”

The insistence on facts means that a work of art needs to be explained and its context needs to be fleshed out. The wall label becomes an essential part of the work, a didactic lesson. This is the opposite of ambiguity, of course. But read Guston’s statement again; he was tired of a particular kind of ambiguity, which he italicized in the text, but he never once claimed to be in favor of the factual.

I am reminded of two other statements that Guston made in his lecture at the University of Minnesota:

I think that probably the most potent desire for a painter, an image maker, is to see it. To see what the mind can think and imagine, to realize it for oneself, through oneself, as concretely as possible. I think that’s the most powerful and at the same time the most archaic urge that has endured for bout twenty-five thousand years.

Guston’s comment casts no judgment about representation or abstraction. He sees a painter as an image maker. An image can be abstract or representational.

After decades of painting and drawing, this is what Guston concluded:

I don’t know what a painting is; who knows what sets off even the desire to paint? It might be things, thoughts, a memory, sensations, which have nothing to do with painting itself. They can come from anything and anywhere.

It can even come from the third act of Our Town by Thornton Wilder, as Miller points out, but with Bennett’s imagination taking that inspiration into the present moment, to our fear and anxiety, and the feeling that we must maintain a vigilant caution. At the same time, Bennett’s painting stays open.

Amy Bennett: Nuclear Family continues at Miles McEnery Gallery (520 West 21st Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through August 16.