Rico Gatson | The Brooklyn Rail

By Mary Ann Caws

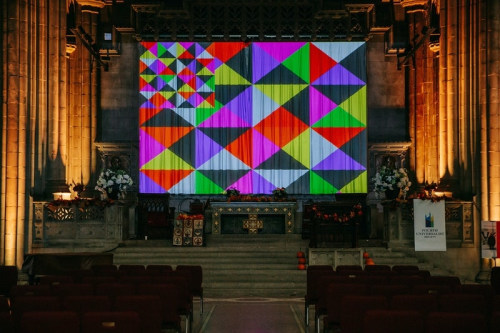

Installation view: Sacred Spaces, Fourth Universalist Society, New York, 2021. Courtesy Fourth Universalist Society and Loretta Howard Gallery. Photo: Peter Beer, CT.

Sacred Spaces

"Loretta Howard and her gallery have planned this amazing and ongoing celebration of the way in which art can enhance an entire life of religious ritual. This immediate burgeoning of new work, relating, in the case of the great Greek artist Antonakos, to Byzantium and the sacred gold background, responds to just what we might have been suffering lately, in view of the crises in the world beyond the building whose art we are celebrating. Just as I was beginning this piece, I re-read in the New York Times of Aug. 25, 2021, about the book of Roxane Van Iperen, “The Sisters of Auschwitz,” in which she points out the importance of “creating new symbols to make sense of what’s happening.” That is surely the point of the most relevant art: making sense and symbols of whatever world we live and think and move in. How we deal with the confrontation of our inner spirit and our outer motions: how we think of the circulation between our consecrated spaces we choose to dwell in imaginatively and occasionally, or sometimes often. There is a sort of weekly and ongoing joy in repeating an event in a set-aside space for a sharing of community and hopeful gathering.

Our thought of gathering to create our own path even as we sit or stand together signifies surely the relation of what we conceive of as a dominant atmosphere for our living domestic or interior space to our ongoing and alas often over-detailed daily doings: what to conceive of and undertake the making of for lunch or supper, and how to nourish those who depend upon us for their own living interior and exterior space. We might wish for and believe in a collective liberation through the mingling of art and spirituality, in a sanctuary of peace and wisdom. Beauty helps massively. As might some rituals, such as the lighting of a candle in a chalice, to mark the start of a repeated event, new every time in its new hope, and then its extinguishing, not like the extinguishing of a wish but simply this particular moment. Its own opening to multiple interpretations and perspectives on the art displayed composes part of the space. Abstractly, as we say and see, but no less figuratively and concretely.

If, at the present moment, I am insisting on how a chapel relates to the larger space of a church, let me stress not just in addition to but alongside my fascination with the Stephen Antonakos gold and gleaming shapes—let me equally stress not just gilded (surface, sometimes signaling something underlying and deeper) but gold in the real sense of genuine. I love equally the smaller frames or rectangular shapes, like letters sent into space—as if we were re-entering a series of letters sent into bottles, or otherwise, into the ocean of eternity. How not to read them as messages to all of us wherever we receive them, about whatever we might care most about?

So I needed to approach first what is at present more approachable than the orthodox saints celebrated in the window above the chapel altar. Saints we know by particular names, stained glass windows we know from our past in so many cathedrals in France and wherever, and consequently we address them by name, whatever our religion. Already the location above the altar speaks—I won’t say shouts— for that sound clashes with the innate silence required for the equivalent of prayer. For all souls, not just some selected ones.

Now Ronald Bladen’s top-opening V, or Very Victorious sign, delighting in its Singular Simplicity, V, like our arms outstretched, is the perfect answer spatially beneath but in no way beneath the saintliness so colorful above, as if at once echoing the— yes, I can say it— triumph of what matters to us all. In its large volume, it embraces a cognitive energy and a safe environment, as the living and universal symbol of peace and togetherness. It invites experiment and aims at a higher consciousness. So that, THAT, is the universalist message, the all-of-usness of us, as in we and the world beyond.

In Rico Gatson’s immense construction of triangular shapes above the main altar, we are invited into a space of amazing radiance: black for Black liberation, red for victorious battling against un-understanding, purple for the royalty of beauty, yellow for the sunlight piercing through our frequently surrounding darkness and gloom. The glorious triangles go far past their shape to their assembled meaning, singular or plural or religious significations because of their intricate and supremely luminous appeal to the mental and psychological senses within this sacralized space celebrating a universal communion of like spirits. Nothing of value, I say to myself and anyone who might listen, is excluded: everything possible is invited to be here."