TRACY THOMASON | BOMB MAGAZINE

Back to the Cave: Tracy Thomason Interviewed

30 SEPTEMBER 2020

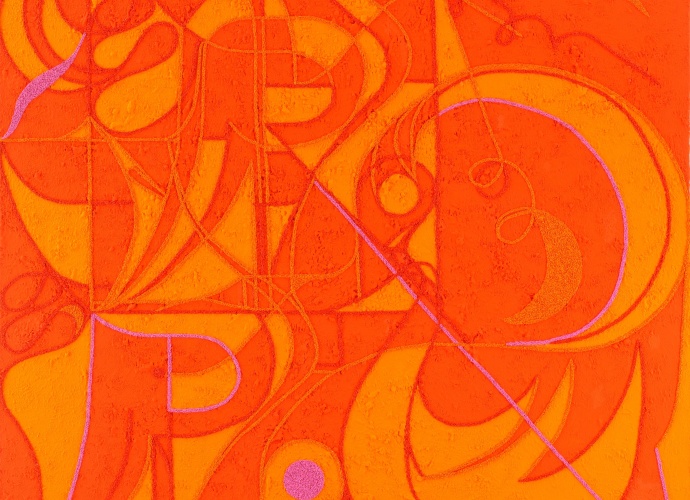

Tracy Thomason, White Rabbit, 2020, oil and marble dust on linen, 20 × 16 inches. Photo by Matt Grubb. Courtesy of the artist and Marinaro.

EK: You are reinterpreting the painting through the lens of now. It seems like an interesting portal for you to the past and future.

TT: I come from a lineage of artists; my great-grandmother and mother are both artists. Showing up to the studio every day and doing these gestures allows me to connect with them on a psychic and physical level that I am not able to achieve right now. My grandmother practiced Buddhism, which has impacted my interest in nonhierarchical thinking that in turn lends itself to how I want formal devices to live in the work. Working to create balance within the paintings comes from her. She did a great deal of philosophical growth in her sixties. She joined a Zen Buddhist compound and made art in New Mexico for the rest of her life. She lived in a trailer with her paints and pottery and a bunch of chickens. (laughter)

EK: So that is always in the back of your mind as an option?

TT: Yes, there is the option to check out. My grandmother used to mail me sand and dirt from New Mexico, and we’d send drawings back and forth. When she passed she had all of the drawings I sent her cremated with her. I feel like that is what I am trying to do with the work.

Installation view of Tracy Thomason: White Rabbit, Marinaro, New York. Photo by Matt Grubb. Courtesy of the artist and Marinaro.

Emily Kiacz: Are these works pre- or post-COVID-19?

Tracy Thomason: I would say that half of them were started months before COVID, but in the past couple of months I finished up the show about fifty-fifty.

EK: What has it been like making work during this crisis?

TT: Thinking about Sisyphus, I can’t go on, but I must go on. I was fortunate to be working toward a show.

EK: Once the work is made and out in the world, do you feel like looking at art can be a healing experience?

TT: Yes, I am personally looking for something outside of myself, and that is a very simple and straightforward thing art can do. Currently, I am working on some larger-scaled works that are heavily built up from pigment and stone, almost mimicking something more environmental and experiential. It’s all about going back to the cave for me.

Installation view of Tracy Thomason: White Rabbit, Marinaro, New York. Photo by Matt Grubb. Courtesy of the artist and Marinaro.

EK: The new work is denser; the tactile quality is more present. Viewers looking at them now will have an interesting experience, since we are all starved for contact.

TT: We are realizing the sensuality, and lack of it, within the no-contact world. There is this unfair aspect to artmaking where if something is hung in a sterile space you aren’t supposed to touch it. I have a physically direct connection with the work where it feels cold because it is fifty percent stone. There is this transference of heat that I notice when my arm rests on places that aren’t wet paint. This lends itself to figuring out how to have humanity within an inanimate object, a reminder of aliveness. If we are in this time in which we cannot connect with each other, I can imbue that longing in the work with the labor, touching, brushing, and digging.

EK: Before it felt like surface and image dictated color in your work, but now it seems like surface and color create the image. Do you think that the visual hierarchy has changed in that color and surface are coming together to create the image?

TT: Absolutely. The paint is a layer, and it happens to be color; but it’s not about the expression of the self through a singular brush stroke. It relates back to the school of thought that we were taught by our feminist mentors that the paint is the skin. It has a duality within skin and earthen landscape.

EK: Making your own materials results in a wonderful feeling of self-reliance.

TT: When I started with this process a few years ago, scientists had newly reconsidered Lucy, the first woman. I was thinking a lot about early humans, and I found myself alone in my windowless studio among my collection of bags of stones and marble dust. As I was reading about this prehistoric woman, I started banging the rock on the ground and performing these intuitive gestures to grind it back into a pigment; then I incorporated it into paint and ground some more. I found myself becoming an imagined version of her that just happens to make paintings.

EK: It makes me think of Lascaux, a good reference point for starting a painting process.

TT: It’s about diving into the ground as a space to look versus an ethereal space. Dealing with abstraction is another option. We can look up to the sky for some sort of omnipotence, but what if we just look deeper into the space that we are inhabiting? Which makes more sense to me.

Installation view of Tracy Thomason: White Rabbit, Marinaro, New York. Photo by Matt Grubb. Courtesy of the artist and Marinaro.

EK: How do you arrive at the forms in your paintings?

TT: I am a believer that our bodies are smarter than our brains and tell us what we need. I tap into this by making quick, preparatory drawings in which my hand has to move faster than doubt. Conversely, I think the slowness of my process gives me time to think about what gestures we make when our hands are telling us about our minds. The shapes of the organs are the dictating synapses. I picture the brain and the tongue vocalizing the image, which allows me to create forms that allude to those things. The materiality and ideas are both raw and open-ended. How do you create forms within the leftovers of the work?

EK: The space in your work is so specific in that the depth is not always dictated by the surface structure. Do you decide this intuitively?

TT: The more symmetrical works allude to the body where space is anchored from a central line or spine. It starts to mirror something that is more known within myself. However, when the composition is more off-kilter and there is a more heavily built surface, I am grappling more with thought spaces. Areas that are more unknown require more physical work and materiality.

EK: What happens when a painting goes in the wrong direction?

TT: I can always worm my way out of a failing painting. If something feels incredibly awkward, I am driven to find out why.

EK: How do you know when they are finished? With such a meticulous process, do you need time to back away and take in the image?

TT: They kind of finish themselves. I make drawings first, so I am aware of the architecture of the work beforehand. I make blueprints with chalk pastel on interfacing, then I do a transfer. The forms rarely deviate. A lot of the intuiting happens through color, fill, texture, and height of the relief. Sometimes a painting will sit for a month, and I will add an extra red line one centimeter to the left of a form, and it will create the needed balance. When the work tells me what painting to make next, then it resolves itself. When it points to the next painting, I say to myself: This one is wrapping up.

EK: The forms are repetitive but evolve from painting to painting. Can you talk about this green and blue painting, White Rabbit (2020). It feels different from the other works.

TT: Being stuck in New York City during COVID, I’ve been starved for some kind of experience with nature. As a result, I wanted to synthesize this experience I wasn’t having in my studio. Initially I thought that was where this “new palette” was emerging from, but then I realized I was riffing off this painting of my grandmother’s called White Rabbit that I wake up seeing every day in my apartment. It was painted in 1968 in response to the Jefferson Airplane song released the same year. It’s a trippy painting of Alice in Wonderland lying in a field surrounded by mushrooms with a rabbit looking over her. I think I probably wanted to feel her presence these past few months. The formality has seeped in the work, but I’ve also been thinking about psychedelia and expanding the mind along with considering its relationship to civil unrest and social metamorphosis.